Why we think schools are key to fixing America's voter turnout challenges

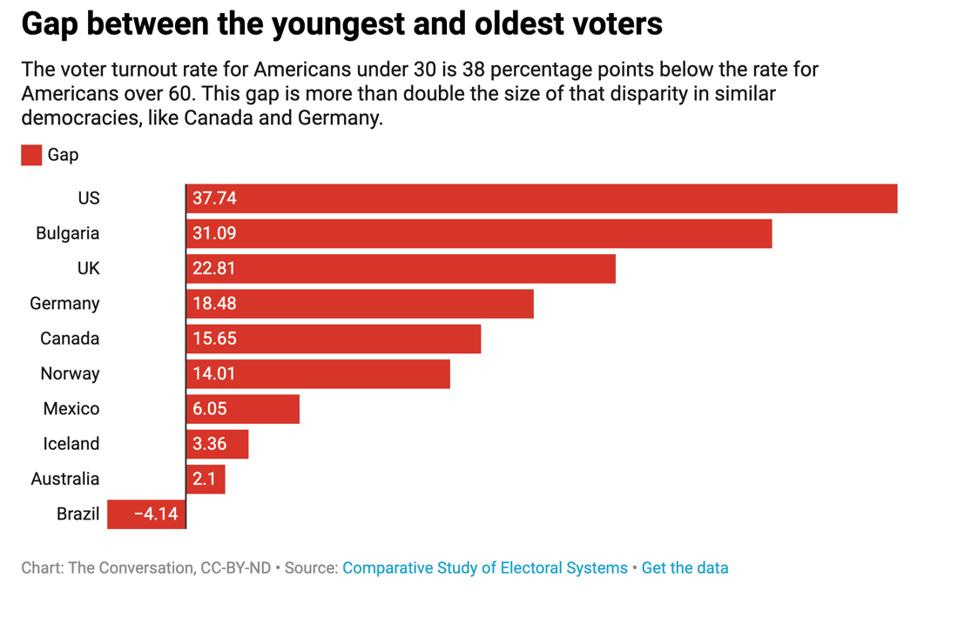

America has one of the world's largest gaps in participation between younger and older voters. It also has a uniquely complex political system for voters to navigate. New voters must learn to use it.

At CDCE, we are committed to working with our colleagues across disciplines in the Maryland Democracy Initiative to address the grand challenge of mobilizing colleges and schools to welcome all new voters. We have been using every strength we have as a university to do this. We are mobilizing our top students to work in high impact internships, rushing new experiments and research into the field ahead of the election, and using our campus to convene leaders working towards 100% student voting.

This Monday, we are thrilled to be hosting 40 of the nation’s most influential and accomplished leaders working to improve and expand voter education programs in high schools at the National High School Voting Summit. These leaders, who CDCE Senior Fellow Jahnavi Rao convenes monthly in the New Voters Collaborative, are working together to set strategy, launch new research projects, and establish shared metrics for evaluating programs mobilizing high schools to welcome all new voters.

The New Voters Collaborative is a nonpartisan coalition of over 30 organizations dedicated to increasing the voting participation and civic engagement of high school students nationwide. The collaborative convenes monthly to discuss critical topics and strategies in high school civic engagement. You can read their latest op-ed in Teen Vogue on how high school students can get involved in the 2024 election here.

We are committed to serving this crucial interdisciplinary knowledge community. In order to serve the New Voters Collaborative, we think it’s important to be explicit about why we think schools are particularly key to overcoming America’s voter turnout challenges. America has one of the world’s largest gaps between newer and more experienced voters (and that gap is even larger for primaries and municipal elections). America also has one the world’s most difficult political systems for voters to navigate. We vote far more often and for far more offices than other democracies. And those elections are governed by a patchwork of over 8,000 local election administrators and election laws that vary across all 50 states, DC, and the territories.

New voters must learn how to vote. Schools can teach them.

We are not born knowing how to vote. New voters must learn how to vote. New voters need to learn how to navigate the logistics of registering and getting a ballot in the place they live. New voters need to learn about how the races and questions on their ballots connect to the issues they care about. And new voters need to learn how to use their votes to express themselves strategically and align themselves with constituencies that can hold power accountable. As Jan Eichhorn and our colleagues in the Vote 16 Research Network have shown in international contexts, new voters can learn these skills in school and strengthen democracy in their communities. In the United States, where the learning curve new voters face is much steeper, there is even greater need for schools to pro-actively provide opportunities for new voters to learn how to vote.

Schools have unique strengths for teaching new voters how to vote.

Our colleagues in political science have done extensive work to study what happens when various types of institutions and organizations try to mobilize and educate voters. There are whole subfields of political science dedicated to studying what campaigns (and other organizations in what Daniel Schlozman and Samuel Rosenfeld call “the party blob”) and election administrators can do to expand voter participation. We have contributed to these subfields and seek to build on them with this line of work. Their seminal insights about the importance of social pressure in driving voter turnout or the ways that some policies like election timing, same day registration and pre-registration, are particularly impactful for new voters have been powerful and influential. There are aspects of America’s voter turnout challenges that can be addressed by campaign marketing and policy change.

But we feel schools are capable of teaching new voters how to vote in unique ways. Just like all the car ads in the world can’t actually teach you how to drive, new voters still need focused time guided by educators or experienced peers to learn how to vote. And schools can provide that kind of focused time in ways that few other institutions can. Certainly in our age of “hollow parties,” it is unlikely that any political party or para-party organizations will achieve the kind of reach and scale to provide this kind of service sustainably to all new voters. And while election administrators could conceivably take on a much larger role in voter education, that is exceedingly unlikely as the costs of running elections continues to outpace the growth of public funding for election administration.

That leaves schools as the crucial institution where almost all new voters can access the focused and guided time they need to learn how to vote. Schools provide an unparalleled opportunity to reach new voters of all races and ethnicities. Schools are institutions with extraordinary potential to promote an inclusive democracy for all.

What we are learning from colleges that Ask Every Student

As often happens with research, a lot of the most important insights about the potential of educational institutions to teach new voters have emerged from the observations of practitioners in the field. One of the most important insights informing our work with the New Voters Collaborative comes from our partners at colleges and universities working to help new voters learn how to vote. They started to notice that there were really significant variations between the campus-wide voting rates of institutions that intentionally provided focused time to learn how to vote and those that did not. While that focused time might be delivered in very different ways at a small private college and a large community college, the insight about the importance of focused guided time across all campus contexts has been extraordinarily powerful. Since 2019, hundreds of institutions across diverse contexts have joined the Ask Every Student initiative and used these insights to develop scores of strategies applying them in diverse campus contexts. When the New Voters Collaborative convenes at the UMD campus on July 8th, we are excited to work with them to apply what we have learned about focused and guided time from Ask Every Student to high school contexts.

How this argument about the importance of schools informs UMD’s work with the New Voters Collaborative

Clearly articulating why we think schools are key to addressing America’s voter turnout challenges will help us serve the New Voters Collaborative in several key ways.

Guiding interdisciplinary literature reviews: One of the most powerful ways universities can serve knowledge communities like the New Voters Collaborative is by synthesizing research from across disciplines and surfacing key actionable insights for community partners. We have seen great results from the work we did last year about action planning to inform campus planning for the 2024 election and from our forthcoming work about public sector workforce recruitment which is informing our research on the elections workforce. We think this argument about the importance of schools could point us towards powerful insights both from our Maryland Democracy Initiative colleagues in the College of Education and from UMD experts in other areas like medication adherence.

Establishing a more holistic research agenda: Political science has made extraordinary advances over the last 25 years by using field experiments to see how much voter turnout increases in response to particular interventions. While these experiments are quite precise in measuring whether something increases voter turnout, they often tell us less about why an intervention increased turnout. By articulating this hypothesis about the mechanisms by which we think schools can increase turnout (providing focused guided time teaching new voters how to vote!) we hope to expand the scope of our research agenda to include strategies for mobilizing schools to provide all new voters with focused and guided time learning how to vote.

Building the evidence base for thoughtful metrics: One of the most important challenges that has been raised by members of the New Voters Collaborative is the need for an evidence base to drive thoughtful metrics that members can use to evaluate their own work and justify philanthropic investment. Metrics based on an evidence base focused on campaign tactics are not going to fit school contexts where educators are building systems that teach new voters how to vote every year rather than setting up a temporary operation to mobilize voters in one election. Counting the number of registrations an organization gets from one voter registration drive doesn’t tell us if they did it in a way that makes that drive a recurring part of the school calendar. We seek to translate the evidence base we are building around how schools teach new voters how to vote into thoughtful metrics in collaboration with our partners in the New Voters Collaborative.

The Upshot

We believe schools are key to fixing America’s voter turnout problems because they can provide new voters with the focused guided time they need to learn how to vote. We believe schools are particularly important in the United States because of our uniquely complex and varied political system. We are using this hypothesis and the research that informs it to help our colleagues in the New Voters Collaborative strategize, develop new research projects, and build confidence in new metrics for program evaluation. And we WELCOME new partners in this work both from the UMD community and beyond. Please reply to this email to get in touch and be a part of this work!

Sam Novey is Chief Strategist at the UMD Center for Democracy and Civic Engagement.